When your mom said you had to eat the carrots on your plate or swap them for broccoli, there was never an option of, “you know what, Mom? I’m not going to eat a vegetable tonight” (If only it were that easy). Instead, you had to buck-up and evaluate your options. In this case, the lesser of two evils. Yet, so often, choices are presented without regard for the realistic alternative. The important question is not, “do I want to eat carrots or not?” Rather, it is, “do I want to eat carrots or broccoli?”

When you are prepared, the best option is usually sticking with the status quo. If there are carrots on your plate and you know you have to eat a vegetable, maybe stick with those instead of panicking and opting for the broccoli. But, there is one factor that inherently makes people ditch the status quo and unwisely opt for something else. That is the fear factor. No, not the show hosted by Joe Rogan where contestants would sit in bins of snakes or eat Rocky Mountain Oysters. Rather, we’re talking about the natural instinct we have to take action when we expect adversity is on the horizon. If poorly prepared, this makes sense and is a great benefit to our survival. Get out of the hurricane’s path. Swerve to miss the deer in the road. You get the idea. However, sometimes we can let fear drive us to make unwise decisions. We swerve too far, missing the deer but driving the car off the bridge. Or, we decide to not drive at all for a few months. We avoid the immediate risk, but bring about a whole host of other problems.

Imagine if before the NBA Finals, both teams began trading away all of their players for new ones. After all, they are about to play an incredibly good team, and the series is going to be tough! There will be adversity. Heck, probably even lose at least a game or two. But these teams would be forgetting that they already have great players, which is what got them to this point in the first place. Worse yet, one team decides to forfeit to avoid the potential agony of losing the series. Investors often treat their portfolios the same way. When they see a rough patch on the horizon, they automatically look for something else. Often times, this is cash or a money market. Less risky, less volatile. Completely avoid the rough patch at all costs. In a vacuum, this strategy is sound. But as we know, the world is anything but a vacuum. Avoiding a potential short-term rough patch often directly leads to a long-term nightmare.

Just ask Kevin Cash, manager of the Tampa Bay Rays. In the sixth inning of Game 6 of the World Series, Cash pulled starting pitcher Blake Snell from the game, despite absolutely dominating the Dodgers and only having a pitch count in the 70’s. Cash’s rationale for the move is that he didn’t want Snell to face the top three hitters of the Dodgers lineup again (who was a combined 0-6 with 6ks against Snell). If there were an option to simply not have anyone pitch to these hitters again, Cash’s logic is sound. But SOMEBODY for the Rays was going to need to throw the ball over the plate to these hitters. Cash was in a position of power, he just didn’t realize it. He could stick with his current dominant pitcher, or roll the dice with someone else out of the bullpen. Being in a position of power allows one to not make a change. The best option is the current option. In this case, Cash’s options were 1. go to a reliever , or 2. stick with the starter, Snell. On that night, Blake Snell was the best pitcher on planet earth. But, operating out of fear led Cash to make a panic move. He felt he had to do something to help his team, when in fact the best option (especially in hindsight) was to take no action at all. When we get nervous of what lies ahead, humans often cope by taking action. It makes us feel better, more in control. We are preventing disaster! Kevin Cash’s reason of not wanting Blake Snell to face those dangerous Dodgers hitters again is hard to argue with. As it turns out, those hitters definitely didn’t want to face him again, either! Remember, 0-6 with 6ks combined. But I digress… For Cash to weigh Snell facing those hitters versus Snell not facing them was not an accurate comparison of his choices. Rather, it would be Snell facing those hitters again, or a reliever entering the game to face them. THAT was the decision. It was going to be a daunting task for whoever was on the mound for the Rays.

It’s convenient that the Rays manager is named Cash, because this story directly relates to investing decisions that millions make every day. As the market hits all-time highs, the whisperings of impending doom start to trickle in to the mind’s of investors. Stick with their current investments they hold, or is it time to get into cash?

Markets crash to varying degrees, we know this. After all, withstanding volatility is the price of investing in equity markets. Those that wish to invest but not pay this fee usually attempt to do so by “timing the market”. However, this often results in an investor doing what Kevin Cash did. They sell too early, and are stuck sitting in cash as the market continues to experience positive returns. They let fear drive decisions, blinding them to the fact that maintaining their current strategy is potentially the best option. After all, it’s our instinct to respond to fear with action… Do something! Just make it better! Outmaneuver and outsmart the competition. So what does this often look like?

Let’s say a nervous investor decides they are going to sell their stocks and move into cash, so they can proudly tell their friends of their wisdom as the market declines and they wait to buy-in at a lower point. This sounds great, just as great as no Tampa Bay Rays pitcher having to face the Dodgers best hitters.

We can call this moment in time the investor sells his stocks, “Point A”. After Point A, one of two things will happen: market returns will be negative, or they will not. If they are not, one of two things will happen:

- With serious FOMO (fear of missing out) the investor admits they were wrong, buys back-in to the market at similar or higher values than when they sold. They lost out on returns between Point A and this new point in time, Point B. Not only did they lose value by buying at higher prices, they’re also right back in the position they were trying to avoid, set-up to go through the next phase of market volatility that hasn’t yet struck.

- The investor stays stubborn and waits for a crash, which may or may not bring values below point A. Even if they do get below Point A, will the investor feel comfortable buying back-in during such volatility?

But what if the investor is right, you say? What if they do time it well and the market does crash right after they sell. Well, once again, one of two things will happen:

- Investor buys back in at a point lower than Point A.

- Investor keeps waiting, sure that the market has more room to fall. They don’t get back into the market until it is too late, and they likely don’t get back in until levels approach Point A. At best, it is a wash for this investor.

Not many people achieve result #1 of this scenario, as nobody wants to buy back-in too early and experience some of the market correction they set out to avoid. So, #2 is all too common. And keep in mind, that’s only IF the investor is right at Point A and times the market well. Of these 4 scenarios, only one (25%) potentially turns out in the investors favor, and it’s often the least likely to occur. So, it’s no wonder that a Fidelity study found that the best investors on their platform were “either dead or inactive.”

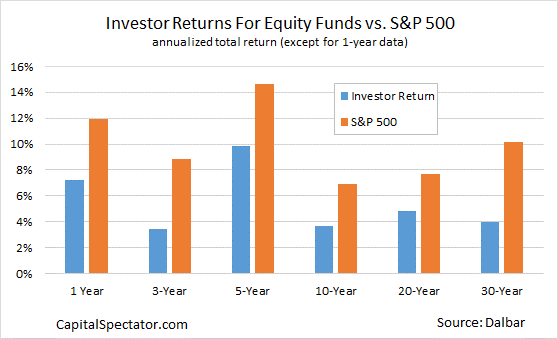

“Investors so often cost themselves money because the behaviors elicited by short-term focus are almost always irrational….While many investors set a course of action that is based on a well-planned rationale and considers the full time horizon, those plans can take a back seat when fear or exuberance sets in.” (Dalbar)

Eating vegetables, tough games, good hitters, and market volatility are all going to occur. The only way to avoid this is by not eating healthy food, not playing the game, and not making long-term investments. You can seek to avoid unnecessary risk, while acknowledging you’ll never eliminate all risk. If you have a solid long-term investment plan (or dominant starting pitcher), you can afford to operate from a position of power when evaluating risk. Perhaps fine-tune your allocation to make sure you’re properly diversified. It’s the equivalent of going over your scouting report with your team and putting in a few new plays, rather than undertaking a roster overhaul. After all, when you have prepared and are invested in appropriate assets (or starting pitching), sometimes the best move to make, is no move at all.

References

Dalbar Quantitative Analysis of Investor Behavior Study. https://www.dalbar.com/Portals/dalbar/Cache/News/PressReleases/QAIBPressRelease_2019.pdf